Financial Stability Report - December 2020

-

Related links

Covid and the economy

The financial system has helped many households and businesses weather the disruption from Covid.

Bank resilience

Major UK banks are strong enough to keep supporting UK households and businesses through this difficult period.

UK and EU relationship

The UK financial sector has prepared for the end of the transition period to limit disruption to financial services.

Section highlights

Risk overview: UK households and businesses have been supported by the financial system to help them weather the economic disruption associated with Covid.

Since the start of the Covid pandemic, businesses have raised substantial funds from banks and financial markets.

Businesses, with the support of government guarantees, have borrowed £80bn so far this year, compared to £20bn by this time last year.

There are a number of risks ahead, including further disruption from Covid and the transition to new trading arrangements between the UK and the EU.

Bank resilience: UK banks are strong enough to support households and businesses through this difficult period.

Banks have high levels of capital, allowing them to absorb very big losses while continuing to lend.

By protecting the economy, it is in banks’ own interest to continue to lend.

The FPC lowered the UK countercyclical capital buffer rate to 0% in March, meaning that banks have more capacity to lend. To help ensure banks plan for the future and support the economy the FPC has confirmed that it expects to keep the rate at 0% for at least another year.

UK and EU relationship: Over the past four years measures have been put in place to limit disruption to financial services at the end of the transition period.

UK authorities and financial sector firms have made extensive preparations over the transition period.

Most risks to UK financial stability have been mitigated.

Some disruption to financial services could arise which does not pose a risk to financial stability.

Whatever the future relationship with the EU, we remain committed to high financial stability standards in the UK.

The UK mortgage market: Our mortgage market measures have helped make households more resilient. And we’re going to review them next year.

The measures have helped to build a ‘safety margin’ so that households are better able to withstand shocks to their jobs, incomes, or mortgage interest rates.

The FPC will review its mortgage market Recommendations in 2021.

Systemic stablecoins and financial stability: The way we make payments is changing.

Developments in technology and the impact of Covid have accelerated changes in how we pay for things.

Stablecoins are digital tokens that claim to maintain a stable value relative to existing forms of money. To be successful as a way of making payments, they must meet standards that ensure they are as safe as existing forms of money.

Financial Policy Summary

The Financial Policy Committee (FPC) aims to ensure the UK financial system is prepared for, and resilient to, the wide range of risks it could face — so that the system can serve UK households and businesses in bad times as well as good.

The UK financial system is supporting the economy during the pandemic

Businesses have raised substantial external financing since the start of the Covid pandemic from banks and financial markets, to help finance their cash-flow deficits. Households’ debt-servicing burdens have fallen during that period, supported by payment deferrals from lenders. The extension of the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme has supported household incomes.

Although there have been encouraging developments on vaccines, the FPC, consistent with its remit, is focused on the range of downside risks that remain. These include risks that could arise from the evolution of the pandemic and consequent measures to protect public health, as well as from the transition to new trading arrangements between the European Union and the United Kingdom.

The outlook for financial stability

Banking system resilience

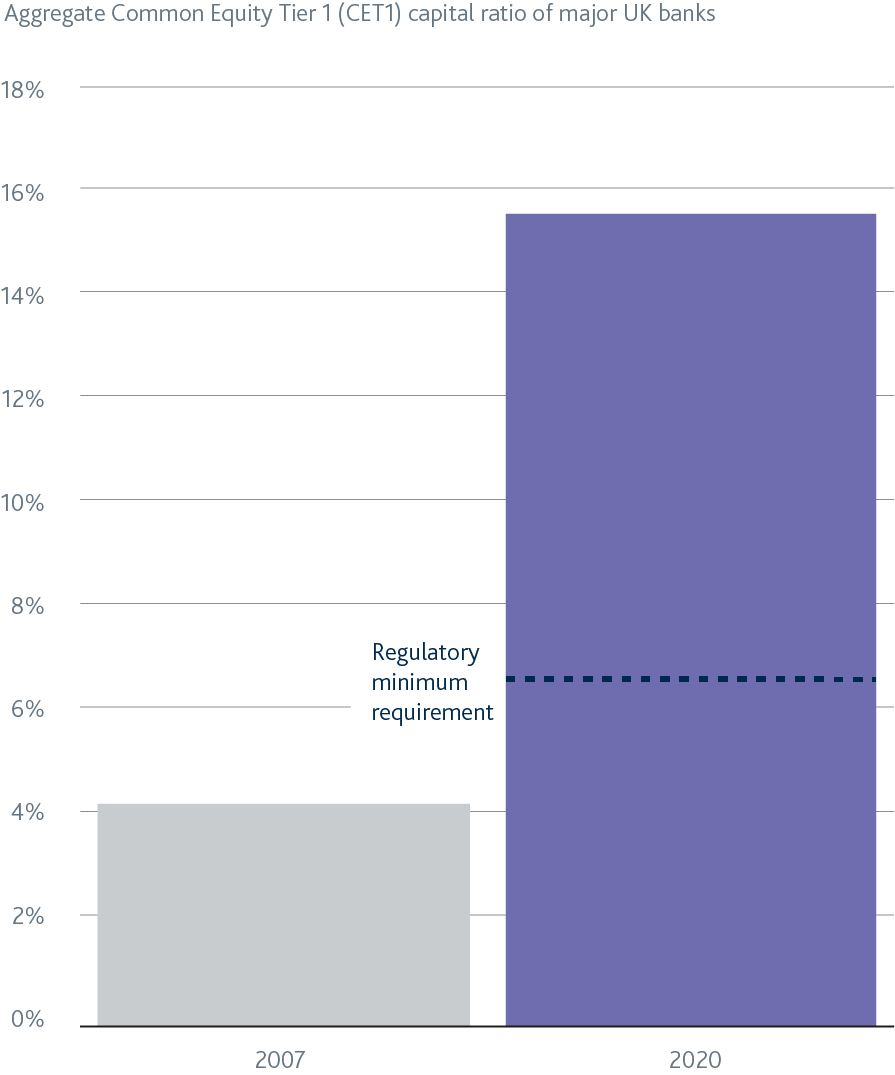

The FPC judges that the UK banking system remains resilient to a wide range of possible economic outcomes. It has the capacity to continue to support businesses and households even if economic outcomes are considerably worse than currently expected. This reflects the build-up of substantial buffers of capital since the global financial crisis.

Over the course of 2020, major UK banks’ and building societies’ (‘banks’) aggregate Common Equity Tier 1 capital ratio has increased to 15.8% at end-September, which is over three times higher than at the start of the global financial crisis. Over this period, they have provisioned for £20 billion of credit losses, although the effect on the capital ratio is reduced by the transitional relief of IFRS 9.

Some headwinds to banks’ capital ratios are therefore anticipated over coming quarters as unemployment rises, business insolvencies rise from current low levels, and risk weights on banks’ exposures increase. Nevertheless, the major UK banks can absorb credit losses in the order of £200 billion, much more than would be implied if the economy followed a path consistent with the MPC’s central forecast.

The FPC judges that the UK and global macroeconomic scenarios required to generate losses on this scale would need to be very severe with, for example, UK unemployment rising to more than 15%.

The FPC expects banks to use all elements of capital buffers as necessary, to continue to support the economy. Alongside the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), it is taking action to support the use of capital buffers.

The FPC is updating its guidance on the path for the UK countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) rate. It now expects this rate to remain at 0% until at least 2021 Q4. Due to the usual 12-month implementation lag, any subsequent increase is not expected to take effect until 2022 Q4 at the earliest. The eventual pace of return to a standard 2% UK CCyB rate will depend on banks’ ability to rebuild capital while continuing to support households and businesses.

The FPC welcomes the PRA’s intention to return towards the standard framework for bank distributions. This reflects some reduction in the uncertainty related to Covid, and the ability of banks to withstand significant losses. The FPC recognises the importance of a stable and predictable capital framework which provides certainty to banks and facilitates the use of capital buffers where necessary.

Cutting support to the economy to avoid the use of capital buffers would be costly for the wider economy and consequently for banks themselves.

Stability in the provision of financial services at the end of the transition period with the EU

Financial sector preparations for the end of the transition period with the EU are now in their final stages. Most risks to UK financial stability that could arise from disruption to the provision of cross-border financial services at the end of the transition period have been mitigated. The mitigation of these risks reflects extensive preparations made by authorities and the private sector over a number of years.

However, financial stability is not the same as market stability or the avoidance of any disruption to users of financial services. Some market volatility and disruption to financial services, particularly to EU-based clients, could arise.

Market volatility could be reinforced in the event that some derivative users are not fully ready to trade with EU counterparties or on EU or EU-recognised trading venues. Financial institutions should continue taking measures to minimise disruption.

Irrespective of the particular form of the UK’s future relationship with the EU, and consistent with its statutory responsibilities, the FPC remains committed to the implementation of robust prudential standards in the UK. This will require maintaining a level of resilience that is at least as great as that currently planned, which itself exceeds that required by international baseline standards, as well as maintaining UK authorities’ ability to manage UK financial stability risks.

Developments in the UK mortgage market

Mortgage credit conditions remain tighter than at the start of the year, particularly for high loan to value mortgages. This reflects reduced risk appetite from lenders due to the economic outlook, as well as operational constraints in meeting the current high demand for mortgages.

The FPC’s mortgage market Recommendations limit the proportion of new mortgages with high loan to income ratios, guarding against an increase in the number of highly indebted households.

The measures are structural and intended to remain in place through cycles in the mortgage market. The FPC’s last review of its Recommendations in 2019 found no evidence that they were having a material impact on mortgage availability overall since they were introduced in 2014. That has remained the case since.

The FPC periodically reviews its measures, including their calibration. It judges that changes over time in the risks faced by households mean the measures warrant a further review. That is under way and the FPC will report its conclusions in 2021.

Ensuring the financial system is ready to serve the future economy

The supply of productive finance for companies

In order to help limit the degree of economic scarring caused by Covid, work to increase the supply of longer-term, equity-like financing is increasingly important. The Bank, with HM Treasury and the Financial Conduct Authority, has launched an industry working group to facilitate investment in productive finance.

Systemic stablecoins

Stablecoins are digital tokens that claim to maintain a stable value at all times, primarily in relation to existing national currencies. They could provide benefits to users but will be adopted widely and become successful as a means of payment only if they meet appropriate standards and confidence in their value is assured.

The FPC, along with many authorities internationally, is considering the potential effects on financial stability if stablecoins were to be adopted widely. A discussion paper on these issues will be published in due course by the Bank. That paper will also address issues that may arise in connection to the concept of a Central Bank Digital Currency — an electronic form of central bank money that could be used by households and businesses to make payments.

The FPC is also considering how the regulatory system should adapt to assure confidence in the value of stablecoins at all times, while supporting innovation, in an efficient way. Their users must be as sure of their ability to redeem their money in cash, at face value, at all times, as they are with private money — commercial bank deposits — that is in widespread circulation in the UK today.

1: Overview of risks to UK financial stability

UK households and businesses have needed support from the financial system to weather the economic disruption associated with the Covid-19 (Covid) pandemic. The UK financial system has so far provided that support, reflecting the resilience that has been built up since the global financial crisis, and the extraordinary policy responses of the UK authorities.

The Financial Policy Committee (FPC) judges that the UK banking system remains resilient to a wide range of possible economic outcomes. It has the capacity to continue to support households and businesses, even if economic outcomes are considerably worse than currently expected. Cutting support to the economy to avoid the use of capital buffers would be costly for the wider economy and consequently for the major UK banks and building societies themselves.

In order to help limit the degree of economic scarring caused by Covid, work to increase the supply of longer-term, equity-like financing is increasingly important. The Bank, with HM Treasury and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), has launched an industry working group to facilitate investment in productive finance.

Vulnerabilities in the global system of market-based finance were exposed in March. Should the outlook worsen, and markets to adjust abruptly, these vulnerabilities could be exposed again. The FPC continues to advance its work, domestically and internationally, to address the underlying issues.

1.1: The economic backdrop

The impact of the Covid pandemic and the measures introduced to reduce its spread continue to pose risks to financial stability, globally and in the UK.

In recent months, an increase in new Covid cases resulted in governments in many countries reintroducing restrictions on activity to help control the resurgence of the virus. As set out in the November 2020 Monetary Policy Report (MPR), this is expected to weigh on both UK and global GDP.

In November, there was encouraging news on three potential Covid vaccines. But the economic outlook remains exceptionally uncertain. It depends on the evolution of the pandemic and the measures taken to protect public health, as well as the response of households, businesses and financial markets to these developments. There is uncertainty around the nature of and transition to new trading arrangements between the European Union (EU) and United Kingdom.

1.2: Near-term risks to UK financial stability

Companies

Businesses have raised substantial external financing since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic from banks and financial markets, and many may have been able to finance their cash-flow deficits.

Bank staff estimate that UK companies could face a cash-flow deficit in the 2020–21 financial year of up to around £180 billion under the forecast set out in the November MPR, and after taking into account Government action to support businesses announced since then (Chart 1.1).footnote [1] This estimate is materially higher than a typical cash-flow deficit for businesses, of around £100 billion.footnote [2]

Chart 1.1: Many businesses might have been able to finance their cash-flow deficits

UK corporates’ cumulative net finance raised alongside estimated cash-flow deficits (a) (b) (c)

Footnotes

- Sources: Bank of England, Fame (Bureau van Dijk), ONS, S&P Global Market Intelligence LLC’s Capital IQ service and Bank calculations.

- (a) The cash-flow deficit bar considers only firms with deficits. The deficit after exhausting cash buffers assumes firms use up all their available cash. Net finance raised considers UK private non-financial corporates (and excludes some forms of finance, eg private equity) between March and October 2020 (not seasonally adjusted). Some finance raised will not finance deficits, nor be raised by firms with deficits.

- (b) The ‘typical’ cash-flow deficit refers to the aggregate negative cash flows estimated from companies’ latest pre-Covid balance sheet data, measured before dividend distributions and share buybacks. ‘Typical’ finance raised is the average cumulative net finance raised between March and October for 2016–19 (not seasonally adjusted).

- (c) The cash-flow deficit figures shown are the maximum of the estimated ranges (£148 billion–£176 billion and, for the typical deficit, £90 billion–£100 billion). Cash buffers that could be exhausted is the mid-point of the estimated range (£87 billion–£97 billion).

If UK companies with available cash balances before this year used these to finance their cash-flow deficits, this would reduce the estimated deficit to around £90 billion. But the extent to which they would choose to do so is uncertain; many may prefer to preserve existing cash balances.

Since March, UK businesses have raised over £77 billion of net additional financing from banks and through access to financial markets. Supervisory intelligence suggests the vast majority of net bank lending over that period has been via government-backed loan schemes. Net bank lending to UK small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the year to October was more than 40 times higher than the 2016–19 average. By contrast, larger UK corporates have repaid bank loans in recent months but have at the same time issued equity and bonds. UK businesses’ cumulative net equity issuance in the year to October was over £18 billion — compared to negative cumulative net issuance on average for the same period between 2016 and 2019.

This net increase in finance, coupled with existing cash buffers, may have enabled many businesses to finance their cash-flow deficits in the period up to October. However, some businesses may need additional finance to bridge the renewed disruption to activity since then.

Some businesses may look to access further external finance to help meet cash-flow deficits in the period ahead…

The Government has confirmed that access to its three lending schemes — the Bounce Back Loan Scheme (BBLS), the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme and the Coronavirus Large Business Interruption Loan Scheme — will be extended, to receive applications through to the end of January 2021. This will provide support to qualifying businesses that may require further financing during this phase of restrictions.

Some companies may have already reached the maximum borrowing limit under the schemes. Supervisory intelligence also indicates many BBLS borrowers would have fallen outside lender risk appetites without the guarantee. In November, however, the Government announced that BBLS borrowers could ‘top up’ their existing loan under the scheme if they had originally borrowed less than the maximum amount available to them: staff estimate that this could accommodate an additional £5 billion of lending in aggregate.footnote [3]

Reflecting the uncertain economic environment, the terms on loans not backed by government-backed schemes are tightening. Supervisory intelligence indicates that lenders have reduced loan limits or tightened their underwriting standards for certain sectors.

In addition, a large number of businesses — many of which are SMEs — have made claims for losses related to the pandemic under business interruption insurance policies. The variation in the types of cover provided and wordings used mean it can be difficult to determine whether customers have cover and can make a valid claim. The FCA brought a test case to the High Court to help resolve this uncertainty as quickly as possible, and appeals at the Supreme Court were heard in November. The scope of the test case covered policy wordings held by approximately 370,000 policyholders.

…and unemployment and insolvencies are likely to increase in 2021.

Some companies, particularly those in sectors of the economy exposed to more structural change that has been accelerated by Covid, may face challenges to their longer-term viability. Analysts’ expectations of earnings in three years’ time provide one perspective on those sectors perceived as most affected (Chart 1.2). These companies may be unable, or unwilling, to access additional external finance.

Chart 1.2: Weakness in earnings is expected to persist into the medium term in certain sectors

Analysts’ expectations for listed company earnings in three years’ time, as a proportion of pre-Covid earnings (a)

Footnotes

- Sources: Eikon by Refinitiv and Bank calculations.

- (a) Includes listed companies headquartered in the UK for which at least one analyst has estimated their earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) in three financial years’ time. Chart shows sector averages, weighted by companies’ pre-Covid EBITDA. Pre-Covid earnings defined as the EBITDA most recently reported for an annual period concluding prior to 28 February 2020. Analysts’ expectations calculated as the average of analysts' EBITDA forecasts for each company as of 2 December 2020.

Smaller companies tend to: be more concentrated in those sectors most affected by the public health measures; have seen a greater increase in indebtedness relative to larger firms to date; and also may find their capacity for further borrowing limited because they have already borrowed heavily using the government schemes.

Unemployment is expected to increase in 2021 (see November 2020 MPR), and insolvencies are likely to increase from their current low levels. Insolvencies have remained subdued to date (Chart 1.3). They are a lagging indicator of corporate distress, and changes to the law on winding up petitions (introduced in April) have also reduced the number of insolvencies.footnote [4]

Chart 1.3: Insolvencies have remained subdued to date but are expected to pick up into 2021

Total new corporate insolvencies (a)

Households

The share of households with high debt-servicing burdens fell at the beginning of 2020 H2.

Results from the NMG survey suggested that the share of UK households with high debt-servicing burdens on their mortgages — ie debt-servicing ratios (DSRs) of at least 40% — was 1.3% at the beginning of 2020 H2.footnote [5] This is consistent with the Covid special survey from Understanding Society, which estimates the share at 1.4% in July (Chart 1.4). The share has fallen since May, driven by a faster than expected recovery in households’ earnings, but remains elevated compared with its pre-Covid level of 0.9%.

Chart 1.4: The share of households with high mortgage DSRs has fallen since May

Percentage of households with mortgage DSRs at or above 40% (a) (b) (c)

Footnotes

- Sources: British Household Panel Survey/Understanding Society (BHPS/US), NMG Consulting survey and Bank calculations.

- (a) Percentage of households with mortgage DSR at or above 40% calculated using BHPS (1991–2009), US (2009–19), and the online waves of NMG Consulting survey (2011–20). NMG data are from H2 surveys only, aside from in 2020. Mortgage DSR calculated as total mortgage payments as a percentage of pre-tax income.

- (b) A new household income question was introduced in the NMG survey in 2015. Adjustments have been made to data from previous waves to produce a consistent time series.

- (c) US special survey estimates calculated by adjusting latest mortgage DSRs reported in the main survey for the change in household earnings since January/February reported in Waves 1–4 of the US Covid survey.

The extension of the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) will limit job losses in the near term…

The reintroduction of restrictions on activity in October and November is expected to adversely affect households’ earnings. But the extension of the CJRS to March 2021 will provide immediate support to household incomes and can be expected to dampen the unemployment rate in the near term. The share of private-sector employees on furlough, which reached around 40% in the April/May period, fell to around 8% ahead of the recent restrictions. It reached 15% in the first half of November as employees were once again placed on furlough in response to the restrictions.

…and the extension of payment deferral measures will support households in servicing their debt.

Payment deferral schemes (‘payment holidays’), announced by the FCA and offered by lenders, have also provided a form of forbearance to support borrowers who may be experiencing financial difficulties, by allowing a temporary freeze on mortgage and other loan repayments. They have helped to keep debt-servicing burdens low for UK households. UK Finance data for October suggested a total of 4.4 million payment deferrals had been agreed since the start of the pandemic, with around 320,000 deferrals still in place.

The FCA has extended its payment deferral guidance, with borrowers able to apply for an initial or further payment deferral until March 2021, and to extend existing deferrals until July 2021. This is subject to limitations: for example, the total duration of payment deferrals on a credit product may not exceed six months. This can provide respite for borrowers facing challenging financial circumstances.

Payment deferrals are expected to mostly unwind by the end of 2021 H1, and in any case are limited to six months. With unemployment likely to rise, some households might experience challenges making their debt repayments at the end of deferral periods. It will be important for lenders to work flexibly with borrowers as they resume repayments.

Banks

Major UK banks’ and building societies’ (banks’) capital positions remain strong.

Over the course of 2020, banks’ aggregate Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio had increased to 15.8%. However, some headwinds to banks’ capital positions are anticipated during 2021. This is principally from risk weighted asset inflation, and the reduction in International Financial Reporting Standard 9 transitional relief on the existing stock of provisions as unemployment and insolvencies increase and some assets move into default. Analyst consensus expectations are that major UK banks will incur further credit impairments over the course of 2021.

Nevertheless, the major UK banks can absorb credit losses in the order of £200 billion, much more than would be implied if the economy followed a path consistent with the MPC’s central forecast. The FPC judges that the UK and global macroeconomic scenarios required to generate losses on this scale would need to be very severe with, for example, UK unemployment rising to more than 15%. The FPC judges that the UK banking system has the capacity to continue to support businesses and households, even if economic outcomes are considerably worse than currently expected.

Markets

There remain a number of risks to market functioning — including corrections to prices of risky assets…

Global risky asset prices have been responsive to recent news — picking up in November after the US election and positive results on late-stage tests of three potential vaccines. However, corporate bond spreads appear compressed, despite the uncertain economic conditions, and credit fundamentals (Chart 1.5).

Chart 1.5: Relative to historical levels, corporate bonds spreads are compressed, despite uncertainty

Option-adjusted corporate bond spreads, relative to historical averages (a) (b)

Footnotes

- Sources: ICE/BoAML and Bank calculations.

- (a) Bars show the percentile of the latest observation, relative to historical values. Data is from January 1998, with the exception of adjusted EUR corporate bond spreads starting in March 1998.

- (b) The adjusted credit spread is based on available data. It accounts for changes in credit quality and duration of the index since 1998, but not for changes to rating agencies’ methodologies over time.

…and the risk of fallen angels, where the immediate risk has fallen but remains elevated one to two years out.

Following a sharp increase in downgrades during March and April the volume of ‘fallen angels’ — bonds that have lost their investment grade status — has stabilised. The face value of ‘BBB-’ rated bonds across major currencies with a 50% chance of being downgraded in the next 90 days has more than halved since March. But the expected performance of bonds at a slightly longer — one to two year – horizon has worsened, with the share of sterling ‘BBB-’ rated bonds on ‘negative outlook’ having increased almost fivefold since March.

An increase in fallen angels could potentially lead to sales of such bonds accelerating and a disproportionate tightening in credit conditions. These risks could crystallise earlier if the outlook deteriorates. The capacity of the sterling high-yield market to absorb such sales could still be tested, were downgrade rates to increase.

While financial markets have continued to function effectively since the August FSR…

Financial markets have continued to function effectively since the ‘dash for cash’ episode in March. This episode saw certain markets — including those essential to the smooth functioning of the UK financial system — become severely disrupted, making central bank intervention necessary to restore order.

Bid-offer spreads on long-term gilts — which provide a benchmark for many other borrowing rates relevant to the Government, businesses and households, and are therefore a key component of the functioning of the financial system — have returned to their pre-Covid levels (Chart 1.6). Corporate bond bid-offer spreads are only slightly elevated compared to pre-Covid levels. And the sterling repo market, an important source of liquidity for financial institutions, also has been stable with spreads remaining around their historical averages.

Chart 1.6: Bid-offer spreads on gilts and corporate bonds remain stable

Bid-offer spreads for gilts, US treasuries and corporate bonds

Footnotes

- Sources: Eikon by Refinitiv, MarketAxess and Bank calculations.

…it remains crucial to analyse and, where necessary remediate, vulnerabilities exposed in the ‘dash for cash’ episode.

As set out in the August FSR, a number of areas need to be explored to address the vulnerabilities exposed in market-based finance during the March ‘dash for cash’ episode. Such work is necessarily a global endeavour, reflecting the international nature of these markets and their interconnectedness.

In November, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) published its holistic review of the March market turmoil. The report concludes that this episode underscored the need to strengthen resilience in the sector, and sets out a comprehensive workplan for addressing the vulnerabilities that were exposed.

The FPC welcomes the FSB’s report, and the Bank and FCA will continue to work closely with counterparts in the FSB on the next stages of this work to enhance the resilience of the non-bank financial system. The FPC will publish a full update on its market-based finance agenda in 2021 H1. This follows publication of the FPC’s preliminary findings in the August FSR, and will also represent the FPC’s response to HM Treasury’s recommendation to publish a more detailed assessment of the oversight and mitigation of systemic risks from the non bank financial sector by end-2020. Completing this review in 2021 H1 enables the FPC to incorporate the findings of the FSB’s holistic review into its assessment, and help the Bank to feed its findings into the international consideration of efforts to address any problems identified.

Operational risks

While most risks to UK financial stability at the end of the transition period with the EU have been mitigated, some market volatility and disruption to financial services could arise.

As set out in Section 3, most risks to UK financial stability that could arise from disruption to the provision of cross border financial services at the end of the transition period have been mitigated. However, financial stability is not the same as market stability or the avoidance of any disruption to users of financial services. Some market volatility and disruption to financial services, particularly to EU-based clients, could arise.

The FPC welcomes announcements from ICE Benchmark Administration (IBA) and the FCA to support an orderly wind down of Libor benchmarks.

It remains essential to end reliance on Libor benchmarks. In November, the administrator of Libor, IBA, announced that it will consult on its intention for the euro, sterling, Swiss franc, Japanese yen and some US$ Libor panels to cease at end-2021, and for the remainder of US$ panels to cease at end-June 2023; this consultation was published in December. In parallel, US regulators issued supervisory guidance on limiting new use of US$ Libor after end-2021. The FCA also set out, and published consultations on, its potential approach to the use of proposed new powers under the Financial Services Bill to ensure an orderly wind down of Libor, and noted it will co-ordinate with US and other authorities around limiting new use of US$ Libor.

Work is under way across global markets to reduce the risk of disorderly outcomes for contracts that continue to rely on Libor. In October, ISDA published a protocol for legacy Libor-linked derivatives contracts. This provides a readily available avenue to adopt fallbacks into most non-centrally cleared derivative contracts and replace Libor with risk-free rate alternatives, once the fallbacks have been triggered. So far over 1,500 entities worldwide have signed up, including the Bank in respect of its own market activity.

1.3: Ensuring the financial system is ready to serve the future economy

The FPC’s workplan on productive finance is intended to support the sustainability of corporate sector financing.

At the aggregate level, the UK corporate debt to earnings ratio increased from 320% at the end of 2019 to 344% at the end of 2020 H1. Removing impediments to businesses’ access to longer-term, equity-like and potentially more illiquid financing, can support economic growth and financial stability. It could also help to support the Government’s aim to transition to an economy with net zero greenhouse gas emissions. Addressing possible distortions to the supply and intermediation of longer-term productive finance, as set out in the August FSR, is one of many factors that can help pave the way for a higher level of investment.

There have been important developments in this work since August. This includes a new industry working group, to be convened by the FCA, the Bank and HM Treasury to facilitate investment in productive finance. The FCA plans to consult early in 2021 on setting up a framework for a long-term asset fund.

The Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario will resume in 2021.

Every two years, the Bank runs a biennial exploratory scenario (BES), an exercise that uses an exploratory scenario to test the UK financial system against a potential future risk. In May 2020, as part of the Bank’s response to Covid, the FPC and Prudential Regulation Authority agreed to postpone the launch of the BES on climate change risk, due to take place in 2021. On 9 November, the Governor announced that the work would resume, with a launch date of June 2021. The exercise will explore the largest UK banks’ and insurers’ resilience to three different climate scenarios, testing different combinations of physical and transition risks over a 30 year period.

The FPC is taking forward its consideration of risks from payment systems that are or could attain systemic importance in the United Kingdom, including new forms of payments involving stablecoins.

The FPC has set out clear expectations for the regulation of such payment systems and will be developing these further to ensure that regulation of innovative payment systems aligns with the risks they could pose (see Section 5). The FPC supports HM Treasury’s Payments Landscape Review and its planned consultation on the UK regulatory approach to cryptoassets and stablecoins, as well as the Bank of England’s upcoming discussion paper on digital assets.

2: In focus – The resilience of the UK banking sector

The FPC judges that the UK banking system remains resilient to a wide range of possible economic outcomes. It has the capacity to continue to support households and businesses even if economic outcomes are considerably worse than currently expected. This reflects the build-up of substantial buffers of capital since the global financial crisis.

Over the course of 2020, the aggregate Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital ratio of the major UK banks and building societies (banks) has increased to 15.8% — around 9 percentage points above minimum requirements. Some headwinds to banks’ capital ratios are anticipated during 2021. Nevertheless, banks remain well capitalised and able to support the economy.

The FPC expects banks to use all elements of capital buffers as necessary, to continue to support the economy. Alongside the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), it is taking action to support the use of capital buffers. Cutting support to the economy to avoid the use of capital buffers would be costly for the wider economy and consequently for the banks themselves.

2.1: The resilience of the UK banking sector

Banks’ capital positions remain strong, even as they have provisioned for credit losses.

The CET1 capital ratios of the major UK banks have continued to rise over the course of 2020 (Chart 2.1).

Chart 2.1: The aggregate CET1 ratio is more than three times higher than it was before the financial crisis

Aggregate CET1 capital ratio of major UK banks (a) (b)

Footnotes

- Sources: PRA regulatory returns, published accounts, Bank analysis and calculations.

- (a) The CET1 capital ratio is defined as CET1 capital expressed as a percentage of risk-weighted assets. Major UK banks are Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds Banking Group, Nationwide, NatWest Group, Santander UK and Standard Chartered. From 2011, data are CET1 capital ratios as reported by banks. Prior to 2011, data are Bank estimates of banks' CET1 capital ratios.

- (b) Capital figures are year-end, except 2020 Q3.

The aggregate CET1 capital ratio increased from 14.8% at end-2019 to 15.8% at end-September — over three times its pre-global financial crisis level. Banks have provisioned for around £20 billion of credit losses so far this year, although the effect on their capital ratios is reduced by the impact of International Financial Reporting Standard 9 (IFRS 9) transitional relief, which limits the extent to which credit loss provisions taken against assets that have not actually defaulted affect capital. The cancellation of outstanding 2019 dividends in line with the PRA’s guidance, has also bolstered banks’ capital ratios.

2.2: The outlook for bank resilience

Some headwinds to banks’ capital ratios are anticipated in 2021.

Looking ahead, there are a number of factors that are likely to weigh on banks’ capital positions. For example, the credit losses banks have taken so far will be followed over time by an increase in risk-weighted assets as the underlying deterioration in credit quality begins to be reflected in risk weights. And as unemployment and insolvencies rise, and more impaired loans default, the benefit banks get from IFRS 9 transitional relief will fall away. Analyst consensus expectations are that banks will incur further impairments over the course of 2021.

Banks’ market valuations reflect the uncertainty about the economic outlook.

The average UK bank price to book ratio, which measures the market value of shareholders’ equity relative to the accounting value of that equity, has been persistently below one for a number of years now. It fell even more at the beginning of the year as the pandemic hit and profit expectations decreased materially (Chart 2.2). The recent weakness of bank valuations also reflects a material increase in the returns demanded by investors — the cost of equity. The biggest influence on the cost of equity has been uncertainty about the economic outlook. Consistent with this, UK banks’ share prices increased sharply in mid-November, following the news regarding potential vaccines.

Chart 2.2: The average price to book ratio of the major UK banks has been consistently under one, and fell further when the pandemic hit

Major UK banks’ price to book ratio (a) (b)

Footnotes

- Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Eikon from Refinitiv and Bank calculations.

- (a) UK banks are Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds Banking Group and NatWest Group. HSBC’s price to book ratio is adjusted for currency movements.

- (b) The underlying data have been sourced from Eikon from Refinitiv up to 2013, and from Bloomberg from 2014 onwards.

Developments over the course of the 2020 support the view that UK banks’ low price to book ratios are consistent with market concerns over expected future profitability rather than concerns about the solvency of banks. For example, while credit default swap spreads, which capture investors’ views on default risk, rose sharply at the onset of the Covid-19 (Covid) outbreak, they have now returned to pre-Covid levels. That is consistent with the high aggregate CET1 capital ratio for the major UK banks.

Although there are material downside risks, banks are resilient to a wide range of possible economic outcomes…

There are a range of downside risks to the economic outlook (see Section 1). However, even with some near term headwinds to capital, the August 2020 ‘reverse stress test’ suggested that banks would need to incur around £120 billion of credit losses (that is, a further £100 billion of losses beyond those already provisioned for) in order to deplete aggregate end-2019 capital by 5.2 percentage points — the extent of the capital drawdown in the 2019 stress test in which banks demonstrated they could continue to lend.

The FPC judges that the macroeconomic scenarios required to generate such losses would need to be very severe, with UK unemployment peaking at around 15%. This judgement is based on the ‘reverse stress test’ conducted by the FPC in August 2020, which used analysis of banks’ balance sheets and stress-testing data to assess how severe an economic shock would need to be to generate a particular level of credit losses.

In reality, the banking system is able to withstand scenarios even more severe than this. Banks have buffers of capital larger than those set for regulatory purposes; so, based on the end-2019 start point of the ‘reverse stress test’, £120 billion of losses would, in aggregate, deplete only around 60% of the buffers of capital which sit above banks’ minimum requirements. In aggregate, banks would be left with the ability to absorb a further £80 billion of losses arising from further shocks before breaching regulatory minima. In total therefore, the ‘reverse stress test’ demonstrated how the major UK banks can absorb credit losses in the order of £200 billion, much more than would be implied if the economy follows a path consistent with the Monetary Policy Committee’s (MPC) central forecast.

…and the most recent outlook is much less severe than the scenarios to which banks are resilient.

The MPC’s most recent central forecast for the UK and global economies in the November MPR remains materially less severe than the scenarios generated by the ‘reverse stress test’.footnote [6] While the outlook had weakened since August 2020 on the back of the second wave of Covid, three-year cumulative GDP losses in the November MPR central projection were forecast to total around £470 billion (21% of annual 2019 GDP) — lower than the £610 billion included in the ‘reverse stress-test’ scenarios (Chart 2.3). Reflecting the extension of government support measures, the path for UK unemployment was also much less severe, averaging a little under 6% over three years.

Chart 2.3: The central forecast in the November MPR is well within the ‘reverse stress-test’ scenario that would deplete banks’ capital buffers materially

Comparison of key metrics in the November MPR and the August 2020 ‘reverse stress test’ over a three-year period (a)

Footnotes

- Sources: Bank analysis and calculations.

- (a) The distance between the end points shows the proportionate change between shocks in the November MPR figures relative to the ‘reverse stress test’. For example, three year cumulative world GDP losses are roughly half those in reverse stress test so the November MPR end point is roughly half way down the first black line.

2.3: Buffer usability

Cutting support to the economy to avoid the use of capital buffers would be costly for the wider economy and consequently for the banks themselves.

Capital buffers allow banks to continue to support the economy in downturns while also weathering losses. In doing that, the UK banking system can be a source of strength for the economy, helping to absorb rather than amplify the economic shock caused by Covid. It is in banks’ collective interest to continue to support viable, productive businesses, rather than seek to defend capital ratios and avoid using buffers by cutting their lending. If viable businesses are unable to meet their financing needs this could trigger larger corporate losses for banks, deepen the economic stress and have an even greater negative effect on banks’ capital ratios.

To ensure buffers can be used to support the economy, the FPC is updating its guidance on the path for the UK countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) rate. It expects this rate to remain at 0% until at least 2021 Q4. Due to the usual 12-month implementation lag, any subsequent increase is not expected to take effect until 2022 Q4 at the earliest. The eventual pace of return to a standard 2% UK CCyB rate will depend on banks’ ability to rebuild buffers while continuing to support the UK economy, households and businesses. This guidance should give firms clarity that they can use capital buffers as necessary.

The FPC also welcomes the Prudential Regulation Committee’s (PRC) decision to freeze systemic risk buffer (SRB) rates for a further year. The FPC is mindful that banks’ ‘total assets’, the metric used to calibrate SRB rates, have grown significantly during 2020 in part due to the MPC’s expansion of central bank reserves through quantitative easing. Without this action, some banks may have faced incentives to constrain lending to the real economy, in order to avoid sharp increases in capital requirements. The PRC decision supports buffer usability. The FPC intends to revisit this issue in due course, as part of a broader review of lessons learnt from the crisis about how the capital framework has supported lending to the economy under stress.

The FPC further welcomes the PRA’s intention to transition back towards the standard framework for bank distributions (see Box 1). Recommencing some distributions is consistent with the judgement that banks are resilient to, and can continue to lend in, a wide range of economic scenarios.

The FPC continues to support the Bank on its work with international colleagues in the Basel Committee to monitor the situation and assess the extent to which temporary changes to the capital framework may be necessary to promote the use of capital buffers for their intended purpose.

2.4: Next steps

The FPC and PRC will conduct a stress test of the major UK banks and building societies in 2021.footnote [7] The Bank’s approach to stress testing aims to use periods in which the economy is growing to build up banks’ buffers of capital, ready to be drawn on to support the economy in a stress. This is achieved by stress testing banks against a broad, severe and hypothetical stress scenario that gets tougher as debt — and other vulnerabilities that can amplify a recession — builds up.

Once the economy enters a stress, as it has now, the focus changes, with stress tests used to assess if the buffers of capital that banks have built up are large enough to deal with how the stress could unfold. In the first instance, that involves testing banks against the likely effects of the stress. The FPC undertook this exercise in May 2020 through its desktop stress test, see the May 2020 interim Financial Stability Report. This found that banks had the capital buffers to withstand even greater losses than those resulting from the MPC’s plausible illustrative scenario.

The next step, given the uncertain economic outlook in an unfolding stress, is to assess that banks’ buffers of capital are sufficient to deal with the stress, even if it turns out to be more severe than central expectations. The August 2020 ‘reverse stress test’ therefore considered how severe a macroeconomic stress banks could withstand while continuing to lend. Policymakers can then use this analysis to assess how likely it is that banks’ resilience could be compromised, and to identify the point at which further policy actions might be necessary if the economic outlook deteriorated significantly.

The ‘reverse stress-test’ exercise showed that the macroeconomic paths required to deplete banks’ regulatory capital buffers would need to be very severe (Chart 2.3). The FPC judges the scenarios included in the ‘reverse stress test’ to reflect reasonable worst cases for the current economic outlook. Banks therefore have capital buffers that allow them to lend in and remain resilient to a wide range of possible scenarios for the UK and global economies over the coming year.

The aim of the 2021 stress test will be to update and refine the FPC’s assessment. It will test banks’ end-2020 balance sheets to a scenario similar to that generated in the ‘reverse stress test’. It will therefore be a cross check on the FPC’s judgement of how resilient banks are to a reasonable worst-case stress in the current environment and will support the PRA’s objective of promoting the safety and soundness of PRA-regulated firms. There will be no mechanical link from the results to regulatory response. But the outcome of the test will be used to update the FPC’s judgements about the most appropriate ways in which the banking system can continue to support the economy through the stress. It will therefore be used as an input into the PRA’s transition back to its standard approach to capital-setting and shareholder distributions through 2021.

Box 1: Large UK banks’ 2020 shareholder distributions

The Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) made the exceptional request in March that banks suspend distributions, reflecting the uncertainty around the Covid-19 (Covid) shock

At the end of March 2020, the PRA welcomed the decisions of the boards of the large UK banksfootnote [8] to suspend dividends and buybacks on ordinary shares until the end of 2020. At the PRA’s request they also cancelled payments of any outstanding 2019 dividends, even though these banks held capital well above regulatory levels, and above the levels at which prudential regulations would require restrictions on distribution.

This exceptional request reflected the unprecedented levels of economic uncertainty facing the global economy at that time due to the onset of the Covid pandemic. The unprecedented public health measures in prospect at the time would clearly lead to a very marked and widespread drop in economic activity but the extent and scale of these was not possible to forecast at that time. There was uncertainty, also, about the scale of monetary and fiscal responses that would be implemented to support the economy. It was unclear how these factors would impact upon macroeconomic outcomes, demand for bank lending, losses, and ultimately bank capital. Reflecting this overall uncertainty, share prices of many UK banks had nearly halved since the start of the year and wider risky asset prices had fallen sharply. Financial market volatility had surged and there had been severe market dysfunction, including in advanced-economy government bond markets.

The initial global spread of Covid occurred at a moment late in banks’ dividend calendars when dividend distributions they had announced were about to be paid out. Given this timing, the then existing market conditions, the very large and uncertain size of the forthcoming downturn, and the unique role that banks play in supporting the wider economy, the PRA’s request was a necessary precautionary step in order to reduce the possibility of an unsafe depletion of banks’ capital in the face of a risk of unknown dimensions.

The capital retained through this precautionary action contributed around 50 basis points to the aggregate Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio of the large UK banks. However, given the PRA’s actions did not reflect a permanent change in banks’ capital requirements, the capital retained would be available either to support lending, absorb future losses or be distributed to shareholders.

The PRA judges that banks have capacity to make prudent payouts with their 2020 results and intends to transition back towards the standard framework for bank distributions

Notwithstanding the impact of the Covid pandemic on the global economy, banks remain well capitalised and are expected to be able to continue to support the real economy through this period of disruption. The Prudential Regulation Committee (PRC) and Financial Policy Committee (FPC) have now carried out two stress tests of banks’ capital positions and have judged that banks are resilient to a wide range of economic outcomes (see Section 2), including economic scenarios that are materially more severe than current central expectations. Based on these assessments, although some headwinds to banks’ capital positions are expected during 2021, banks remain well capitalised and able to support the economy.

Set against that, economic uncertainty as a result of the Covid pandemic remains high, economic disruption continues and widespread government economic support is still in place. In addition, considerable uncertainty remains about the new relationship with the EU to which the UK will need to adapt in the coming months.

Weighing those considerations, and consistent with the PRA’s view that distributions are an important and necessary part of the functioning of the banking system, the PRA judges that an extension of the exceptional and precautionary action taken in March is not necessary and that there is scope for banks to recommence some distributions should their boards choose to do so, within an appropriately prudent framework.

With the removal of the PRA’s request not to make shareholder distributions, it is for banks’ boards to determine the appropriate level of distributions. Any distributions should be prudent, reflecting the still elevated levels of economic uncertainty and the need for banks to continue to support households and businesses through the continuing economic disruption, even in the event that this disruption is more prolonged and severe than currently anticipated. As a stepping stone back towards its standard approach to capital setting and shareholder distributions, the PRA therefore asks boards, when making their decisions for 2020 distributions, to operate within a framework of temporary guardrails (see PRA statement on capital distributions by large UK banks).

The PRA intends to transition back to its standard approach to capital setting and shareholder distributions through 2021. Under this framework, banks’ boards are responsible for making distribution decisions subject only to the standard constraints of the regulatory framework, including the regular annual stress test. In the meantime, for 2021 dividends the PRA is content for appropriately prudent dividends to be accrued but not paid out and aims to provide a further update ahead of the 2021 half-year results of large UK banks.

The FPC welcomes the PRA’s intention to transition back towards the standard framework for bank distributions

The FPC supported the exceptional actions taken in March, which were appropriate given the unprecedented levels of economic uncertainty at the time. The FPC now welcomes — from the perspective of its own objectives to support the supply of credit to the economy during this stress — the PRA’s intention to transition back towards the standard framework for bank distributions.

The FPC judges that banks are resilient to, and can continue to lend in, a wide range of economic scenarios (see Section 2). Recommencing some distributions is consistent with this judgement. The PRA’s framework of temporary guardrails will help to protect the resilience of the banking system in a wide range of possible outcomes.

The FPC recognises the importance of a stable and predictable capital framework which provides certainty to banks and facilitates the use of capital buffers where necessary. The high returns currently demanded by bank investors (banks’ high cost of equity) primarily reflect the uncertain economic outlook. The transition back towards the standard framework for bank distributions through 2021 should, by reducing any additional uncertainty about the outlook for dividends, help to reduce their cost of equity.

3: In focus – The provision of financial services after the end of the transition period

Financial sector preparations for the end of the transition period with the EU are now in their final stages. Most risks to UK financial stability that could arise from disruption to the provision of cross-border financial services at the end of the transition period have been mitigated. The mitigation of these risks reflects extensive preparations made by authorities and the private sector over a number of years. However, financial stability is not the same as market stability or the avoidance of any disruption to users of financial services. Some market volatility and disruption to financial services, particularly to EU-based clients, could arise. Irrespective of the particular form of the UK’s future relationship with the EU, and consistent with its statutory responsibilities, the FPC will remain committed to the implementation of robust prudential standards in the UK.

The UK’s transition period with the EU will end on 31 December 2020.

The UK left the EU with a Withdrawal Agreement on 31 January 2020, entering an 11-month transition period that will end on 31 December 2020. Negotiations on a free trade agreement (FTA) covering the broad arrangements for trading goods and services between the UK and EU are continuing. The ability to provide cross-border financial services between the UK and the EU will largely be determined by regulatory decisions made autonomously by the UK and EU, distinct from the broader FTA negotiations.

To facilitate continued access by UK households and businesses to financial services provided by EU financial institutions after the end of the transition period, the UK has temporary permissions and recognition regimes in place, alongside temporary powers allowing UK regulators to delay or phase-in changes to UK regulatory requirements. In addition, following its equivalence assessments of the EU, the Government has made a number of equivalence determinations in relation to the EU, with the intention of supporting well-regulated open markets.

Those equivalence decisions will, beyond the end of the temporary regimes and powers, allow favourable regulatory treatment for UK banks’ and insurers’ cross-border activity with the EU, and facilitate UK users’ continued access to EU central counterparties (CCPs) and central securities depositories (CSDs). The Government may make further equivalence determinations in the future.

The EU’s equivalence assessment of the UK is ongoing. The European Commission has stated that it will not assess the UK for equivalence in nine areas in the short or medium term, including MiFIR Article 47, which covers the direct provision of investment banking services across borders.footnote [9] It has provided time-limited equivalence for the UK legal and supervisory framework for UK CCPs and CSDs.

Irrespective of the particular form of the UK’s future relationship with the EU, and consistent with its statutory responsibilities, the FPC will remain committed to the implementation of robust prudential standards in the UK. This will require maintaining a level of resilience that is at least as great as that currently planned, which itself exceeds that required by international baseline standards, as well as maintaining UK authorities’ ability to manage UK financial stability risks.

Most risks to UK financial stability that could arise from disruption to the provision of cross-border financial services at the end of the transition period have been mitigated.

Financial sector preparations for the end of the transition period are now in their final stages. Consistent with its financial stability objective, since 2016 the FPC has identified and monitored risks of disruption that could arise if no further arrangements were put in place for the provision of cross-border financial services when the UK’s trading arrangements with the EU change. The FPC reviewed its checklist of actions that would mitigate risks of disruption at the end of the transition period to important financial services used by households and businesses (Table 3.A). The FPC also reviewed other risks to the provision of cross-border financial services that could cause some, albeit less material, disruption if they are not mitigated (Table 3.B).

As set out above, temporary permission and recognition regimes and other preparations have been made by UK authorities to facilitate UK households’ and businesses’ access to existing and new services from EU financial institutions for a period after the end of the year. UK authorities have also acted to allow UK firms to continue trading all shares on EU trading venues after the end of the transition period.

UK financial institutions have continued to prepare for the continued provision of services to EU users.footnote [10] All material subsidiaries of UK firms have been authorised in the EU and are fully operational and over two thirds of clients of major UK-based banks have now completed the necessary documentation to enter into derivatives trades with EU entities. Many clients are also actively trading from the new EU entities. UK firms also continue to novate existing trades where necessary to ensure clients can manage risks related to ‘lifecycle’ events. footnote [11] The EU has announced its intention to provide relief from margin and clearing requirements for certain existing trades that are novated from UK to EU counterparties before January 2022. If implemented, this would create further time for those trades to be novated without triggering additional requirements.

Reflecting the extensive preparations by UK authorities and the financial sector, the FPC continues to judge that most risks to UK financial stability that could arise from disruption to the provision of cross-border financial services at the end of the transition period have been mitigated.

Financial stability is not the same as market stability or the avoidance of any disruption to users of financial services.

Financial markets can be expected to react to the outcome of the negotiations on arrangements for trading goods and services between the UK and EU.

As reflected in the residual risks identified by the FPC in Table 3.A and Table 3.B, some disruption to financial services could arise. This could particularly affect EU-based clients and customers.

Some participants may not be fully ready to trade with EU counterparties or on EU or EU-recognised venues when EU participants’ ability to trade with UK entities or on UK venues becomes restricted. This could reinforce market volatility.

For example, on the basis of the approach that has been announced by the EU and in the absence of further authority action, EU firms in scope of the EU Derivatives Trading Obligation (DTO) would no longer be able to trade some classes of derivatives, such as certain interest rate swaps and credit default swaps, on UK trading venues, and UK firms in scope of the UK DTO would no longer be able to trade these derivatives on EU trading venues.

Based on transaction reporting data as of October 2020, it is estimated that around US$200 billion of interest rate swap trading that takes place daily in the UK is currently captured by the DTO. Absent a further change in policy, the portion of this covered by the EU DTO after the end of the transition period would be required to be traded on EU trading venues, or trading venues elsewhere recognised by the EU. To put this into context, the 2019 BIS triennial survey of derivative activity, which would include activity taking place on and off trading venues, suggested around US$1.2 trillion of interest rate swaps were traded in the UK daily.footnote [12]

UK-based branches of EU firms would be subject to the UK DTO as well as the EU regime. As a result, these branches would only be able to trade those derivatives captured by the obligation on trading venues in other jurisdictions deemed equivalent by both the UK and the EU.

Firms are preparing to comply with the relevant obligations after the end of the transition period, including by executing some trades currently taking place on UK trading venues in the EU or other jurisdictions if necessary. This would result in fragmentation, and could give rise to disruption if some counterparties are not ready to trade immediately after the end of the transition period.

Other examples of disruption would affect households and businesses. Some UK banks have notified EU-based customers that they will not continue to provide certain retail banking services in some jurisdictions.

Processing payments, including Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) payments, between the UK and EU will require additional information to be included after the end of the transition period, such as payers’ addresses. While banks will generally hold payers’ information for credit transfers originating from their customers, they are less likely to hold it for direct debits, where payments are initiated by creditors. Banks have been putting the necessary information in place. Larger UK firms are generally well advanced in providing the information, but there is less clarity about the progress of EU firms. To the extent that gaps remain at the end of the transition period, they are likely to result in some disruption to both EU and UK customers and businesses seeking to make and receive such payments.

Financial institutions should continue taking measures to minimise disruption, including by engaging with clients and customers.

Table 3.A: Checklist of actions to avoid disruption to end-users of financial services at the end of the transition period

This checklist reflects the risk of disruption to end-users including households and companies if no further arrangements are put in place for cross-border trade in financial services at the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020. The risk assessment takes account of progress made in mitigating any risks. It assesses risks of disruption to end-users of financial services in the UK and, because the impact could spill back, also to end-users in the EU.

Risks of disruption are categorised as low (green), medium (amber) or high (red). Arrows reflect developments since the FPC’s previously published checklist alongside the October 2020 Financial Policy Summary. Blue text is news since then.

The checklist is not a comprehensive assessment of risks to economic activity arising from the end of the transition period. It covers only the risks to activity that could stem from disruption to provision of cross-border financial services.

Risk to UK | Risk to EU | ||

Ensure a UK legal and regulatory framework is in place | The passage of the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018 and secondary legislation has ensured that an effective framework for the regulation of financial services will be in place, and that EU financial services companies can continue to serve UK customers. Following the completion of secondary legislation, remaining EU Exit instruments will be finalised by the regulators to ensure new EU legislation and provisions coming into force before the end of 2020 can operate effectively in the UK following the end of the transition period. The State Aid (Revocations and Amendments) statutory instrument has been made. This ensures the Bank of England can continue to provide certain types of emergency lending, should it be needed in future. | ||

Insurance contracts | The UK Government has legislated to ensure that the 16 million insurance policies that UK households and businesses have with EU insurance companies can continue to be serviced after the end of the transition period. UK insurance companies have restructured their business in order to service the vast majority of their £60 billion of EU liabilities. The European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) has published recommendations to national authorities supporting recognition or facilitation of UK insurance companies’ continued servicing of existing EU contracts at the end of the transition period. | ||

Asset management | Co-operation agreements between the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) and EU National Competent Authorities will apply from the end of the transition period. This enables EU asset managers to delegate the management of their assets to the UK. The UK Government has legislated for EU asset management firms to continue operating and marketing in the UK. And to operate in the EU, the largest UK asset managers have completed their establishment of EU authorised management companies | ||

Banking services | The UK Government has legislated to ensure that UK households and businesses can continue to be serviced by EU-based banks after the end of the transition period. EU authorities have not taken similar action. As a result, major UK-based banks have been transferring their EU clients to subsidiaries in the EU so that they can continue providing services to them. All material subsidiaries are authorised, fully operational and trading. Firms are in the final stages of transferring clients to their EU entities. Over two thirds of clients of major UK-based banks have now completed the necessary documentation to enter into derivatives trades with EU entities. Many clients are also actively trading from the new EU entities. However, some operational risks remain, including if many of the remaining clients seek to switch trading to the EU entities in a short period of time. This could amplify market volatility. The EU has stated that in the short to medium term it will not assess the equivalence of the UK’s regulatory and supervisory regime to its own for the purposes of MiFIR Article 47, which covers investment services. This would have allowed for material cross-border access for investment services, further reducing the residual risk of disruption. | ||

Over-the-counter (OTC) derivative contract continuity | Certain ‘lifecycle’ events may not be able to be performed on UK/EEA uncleared derivative contracts after the end of the transition period and on cleared derivatives contracts between UK clearing members and EEA clients. In the absence of mitigating actions this could compromise the ability of derivatives users to manage risks. There are £16 trillion of uncleared derivative contracts between the EU and UK, of which £13 trillion is currently due to mature after 31 December 2020. The UK Government has legislated to ensure that EU banks can continue to perform lifecycle events on contracts they have with UK businesses. The European Commission has not reciprocated for UK-based banks’ contracts with EU businesses. Some EU member states have permanent or temporary national regimes which could enable lifecycle events on certain contracts to be performed. UK firms are prioritising the novation of at-risk contracts. The European Supervisory Agencies have proposed amendments to EU legislation that, if adopted, would enable certain trades novated from UK to EU entities before 2022 to continue to benefit from relief from clearing and margin requirements, creating further time for those trades to be novated without triggering additional requirements. The EU has stated that in the short to medium term it will not assess the equivalence of the UK’s regulatory and supervisory regime to its own for the purposes of MiFIR Article 47, which covers investment services. This would have mitigated risks of disruption to lifecycle events on the majority of contracts. | ||

Central clearing of OTC derivative contracts | The UK Government has legislated to ensure that UK businesses can continue to use clearing services provided by EU-based clearing houses after the end of the transition period. There are currently £60 trillion of derivative contracts between UK CCPs and EU clearing members, £54 trillion of which is due to expire after December. The EU has adopted a decision to provide equivalence to the future UK legal and supervisory framework for central counterparties (CCPs) until end-June 2022, and UK CCPs have been recognised by ESMA. This will allow UK CCPs to continue servicing EU clearing members after the end of the transition period. The Bank and ESMA have put in place a new co-operation agreement to support this activity. | ||

Personal data | The UK Government has legislated to allow the free flow of personal data from the UK to the EU after the transition period. The European Commission is undertaking an assessment of the adequacy of the UK’s data protection standards. If the EU does not deem the UK’s data regime adequate, both UK and EU households and businesses may be affected due to the two-way data transfers required to access certain financial services. Companies can add standard contractual clauses (SCCs) and binding corporate rules (BCRs) into contracts in order to comply with the EU’s cross-border personal data transfer rules in the absence of adequacy. UK firms are generally well advanced in implementing these mechanisms. Following recommendations from the European Data Protection Board and a statement from the Information Commissioner’s Office, firms are undertaking an assessment of whether SCCs and BCRs need to be updated to comply with EU requirements, and whether further appropriate measures need to be taken where personal data transfers from the EEA into the UK are necessary to ensure the continuity of services. |

Table 3.B: Other risks of disruption to financial services

These risks could cause disruption to economic activity at the end of the transition period if they are not mitigated and there are no further financial services arrangements in place at the end of the transition period. The FPC judges their disruptive effect to be somewhat less than that of those issues in its checklist.

Access to euro payment systems | The Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) schemes are currently used by UK payment service providers (PSPs, including banks) to make lower-value euro payments such as bank transfers between businesses, mortgage and salary payments on behalf of their customers. The European Payments Council has confirmed that the UK will retain SEPA access after the end of the transition period subject to its continued compliance with the established participation criteria. Once the UK becomes a third country, processing payments, including SEPA payments, between the UK and EU will require additional information to be included for the payment instructions to meet regulatory requirements, such as payers’ addresses. While banks will generally hold payers’ information for credit transfers originating from their customers, they are less likely to hold it for direct debits, where payments are initiated by creditors. Banks have been putting the necessary information in place where possible. Larger UK firms are generally well advanced in providing the information, but there is less clarity about the progress of EU firms. To the extent that gaps remain at the end of the transition period, they are likely to result in some disruption to both EU and UK customers and businesses seeking to make and receive such payments until the necessary information is in place. UK firms will also need to maintain access to TARGET2 to use it to make high-value euro payments. UK banks intend to access TARGET2 through their EU branches or subsidiaries or correspondent relationships with other banks. |

Ability of EEA firms to trade on UK trading venues | EU-listed or traded securities are traded heavily at UK trading venues which offer deep liquidity pools for a range of securities traded by UK and EU firms. The EU’s Trading Obligations require EU investment firms to trade EU-listed or traded shares and some classes of OTC derivatives on EU trading venues or trading venues in jurisdictions deemed equivalent by the EU. The UK will also have analogous trading obligations when the transition period ends. ESMA has excluded from the EU Share Trading Obligation EU shares which are traded on UK trading venues in sterling. The FCA has acted to allow UK firms to continue trading all shares on EU trading venues and systemic internalisers providing they have a UK recognised status after the transition period. This largely mitigates the risk of disruption, though a portion of trades currently taking place on UK venues will be required to take place on EU venues in future which could result in market fragmentation. In the absence of further authority action in relation to derivatives trading, EU firms in scope of the EU Derivative Trading Obligation (DTO) would no longer be able to trade some classes of derivatives, such as certain interest rate swaps and credit default swaps, on UK trading venues, and UK firms in scope of the UK DTO would no longer be able to trade these derivatives on EU trading venues. Based on transaction reporting data as of October 2020, it is estimated that around US$200 billion of interest rate swap trading that takes place daily in the UK is currently captured by the DTO. Absent a further change in policy, the portion of this covered by the EU DTO after the end of the transition period would be required to be traded on EU trading venues, or trading venues elsewhere recognised by the EU. To put this into context, the 2019 BIS triennial survey of derivative activity, which would include activity taking place on and off trading venues, suggested around US$1.2 trillion of interest rate swaps were traded in the UK daily.footnote [13] UK-based branches of EU firms would be subject to the UK DTO as well as the EU regime. As a result, these branches would only be able to trade those derivatives captured by the obligation on trading venues in other jurisdictions deemed equivalent by both the UK and the EU. ESMA has stated that it does not consider that a change of its approach to the EU DTO is warranted. The FCA has not adjusted its approach either. They continue to monitor market developments. Firms are preparing to comply with the relevant obligations after the end of the transition period, including by executing some trades currently taking place on UK trading venues in the EU or other jurisdictions if necessary. This would result in fragmentation and could give rise to disruption if some counterparties are not ready to trade immediately after the end of the transition period. The EU and UK could deem each other’s regulatory frameworks as equivalent for the purposes of relevant regulations, thereby comprehensively mitigating risks of fragmentation and disruption. |